Background and Constitutional Context

The independence of the judiciary is one of the most fundamental features of the Indian Constitution, ensuring that justice remains free from political or executive influence. The landmark case of Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association v. Union of India (2015) 6 SCC 408 arose from a constitutional challenge to the Ninety-Ninth Constitutional Amendment Act, 2014 and the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act, 2014.

Before the NJAC, appointments to the higher judiciary — Supreme Court and High Courts — were governed by the Collegium System, evolved through judicial interpretation in the Second (1993) and Third Judges Cases (1998). The NJAC sought to replace the collegium system with a more participatory structure involving the executive and eminent persons. However, its constitutional validity was questioned for allegedly violating the basic structure doctrine, particularly the independence of the judiciary.

Thus, this case became a constitutional battleground between judicial independence and democratic accountability — two essential pillars of the Indian constitutional framework.

Facts and Issues of the Case

The petitioners, comprising the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association (SCAORA) and other legal bodies, challenged the 99th Constitutional Amendment and the NJAC Act, 2014 before the Supreme Court under Article 32, seeking to declare both laws unconstitutional.

The NJAC proposed a six-member commission consisting of:

- The Chief Justice of India (CJI) – Chairperson;

- Two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court;

- The Union Law Minister; and

- Two eminent persons (selected by a committee comprising the Prime Minister, CJI, and Leader of Opposition).

The main constitutional issues raised were:

- Whether the 99th Amendment and the NJAC Act violated the basic structure of the Constitution by compromising judicial independence;

- Whether inclusion of executive and eminent persons diluted the judicial primacy in appointments; and

- Whether Parliament had the constituent power to alter the basic structure by modifying judicial appointment mechanisms.

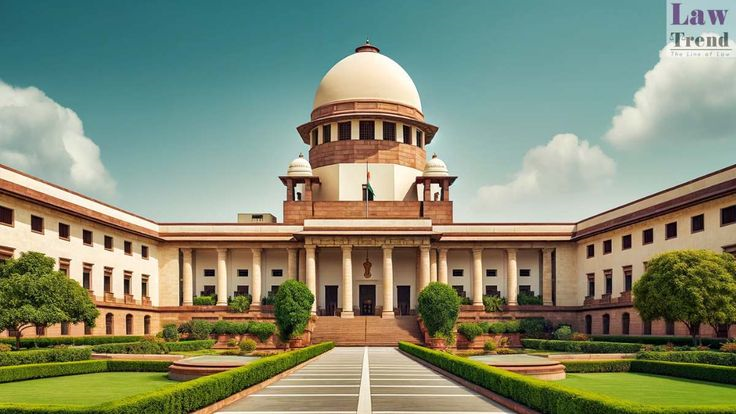

Judgment and Majority Opinion

A five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its verdict on 16 October 2015 by a 4:1 majority, striking down both the 99th Constitutional Amendment and the NJAC Act as unconstitutional and void.

The majority — Justices J.S. Khehar, Madan B. Lokur, Kurian Joseph, and Adarsh Kumar Goel — held that the NJAC violated the basic structure of the Constitution, specifically the independence of the judiciary and the separation of powers under Articles 50 and 124.

Key findings included:

- Judicial independence is the heart of the basic structure and cannot be diluted by executive participation in appointments.

- Inclusion of the Law Minister and eminent persons posed a risk of external influence, threatening the impartiality of judges.

- The Collegium System, though imperfect, was a judicially evolved safeguard to preserve independence from political interference.

The Court thus revived the Collegium System, reaffirming judicial primacy in the appointment and transfer of judges.

Dissenting Opinion and Its Significance

Justice Jasti Chelameswar, the lone dissenting judge, delivered a powerful critique of the collegium system. He argued that transparency, accountability, and checks and balances were essential for judicial credibility. According to him, the NJAC did not destroy judicial independence but rather introduced participatory democracy in judicial appointments.

Chelameswar J. observed that the collegium system had become opaque and unaccountable, functioning without clear norms or public scrutiny. He emphasized that judicial independence cannot mean judicial isolation, and therefore, limited executive involvement would not compromise but strengthen constitutional balance.

Although his dissent did not prevail, it later influenced calls for judicial reforms and improvements in the collegium’s transparency mechanisms, as seen in the subsequent 2016 collegium reform efforts.

Critical Analysis: Strengths and Weaknesses of the Judgment

The 2015 NJAC Judgment reaffirmed the judiciary’s role as the guardian of the Constitution, upholding the basic structure doctrine first established in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973). It protected judicial independence from potential executive overreach, thereby preserving constitutional supremacy.

However, critics argue that the verdict missed an opportunity for systemic reform. While judicial independence is vital, the collegium’s lack of transparency, accountability, and objectivity remained unaddressed. The judgment, therefore, reinstated a flawed system without substantial improvement.

Moreover, the Court’s reasoning reflected a judicial-centric perspective, seemingly distrustful of the legislature and executive. This raises the question — does judicial primacy necessarily equate to judicial independence, or should a balanced approach involving all three organs be constitutionally preferable?

Thus, the judgment highlights the tension between independence and accountability, both equally necessary in a democratic constitutional framework.

Constitutional Principles Involved

The judgment primarily revolved around the Basic Structure Doctrine, which restricts Parliament from altering essential features of the Constitution. The Court held that the NJAC violated:

- Judicial Independence (Articles 124–147, 214–231);

- Separation of Powers (Article 50);

- Rule of Law; and

- Judicial Review (Articles 32 and 226).

By invalidating the 99th Constitutional Amendment, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that even a constitutional amendment is subject to judicial review if it alters the Constitution’s basic structure. This decision reinforced the checks and balances necessary for maintaining the integrity of India’s constitutional democracy.

Real-Time Example and Aftermath

After the judgment, the Collegium System was reinstated. However, acknowledging public criticism, the Court directed the Union Government to prepare a Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) to make the appointment process more transparent.

In 2016, the government submitted a revised MoP suggesting broader consultation, but disagreements persisted, delaying implementation. The tug-of-war between the judiciary and executive continues to this day, particularly over issues like judicial vacancies, delayed appointments, and transfer controversies.

This case remains a living constitutional debate, reflecting the struggle between judicial independence and institutional accountability, and shaping the ongoing discourse on judicial reforms in India.

Mnemonic to Remember — “BASIC JUDGE”

To easily recall the key aspects of the 2015 NJAC Case, remember the mnemonic “BASIC JUDGE”:

- B – Basic Structure: NJAC violated the Constitution’s basic structure.

- A – Article 124: Appointment of Supreme Court judges governed.

- S – Separation of Powers: Breached by including the executive.

- I – Independence of Judiciary: Core principle upheld by Court.

- C – Collegium System: Reinstated as appointment mechanism.

- J – Judicial Review: Applied even to constitutional amendments.

- U – Union of India: Defended NJAC as democratic reform.

- D – Dissent by Chelameswar: Called for transparency and reform.

- G – Guardian Role: Judiciary reaffirmed as constitutional protector.

- E – Executive Role Limited: Law Minister’s inclusion held invalid.

Mnemonic Summary: “BASIC JUDGE” = Basic structure, Article 124, Separation, Independence, Collegium, Judicial review, Union, Dissent, Guardian, Executive.

About lawgnan

Dive deeper into the NJAC Case (2015) at Lawgnan.in — a landmark judgment that redefined judicial independence in India. Understand how the Supreme Court, in Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association v. Union of India, struck down the 99th Constitutional Amendment and the NJAC Act, 2014 for violating the basic structure doctrine. Learn about the Collegium System, Justice Chelameswar’s dissent, and the ongoing debate between independence and accountability in judicial appointments. Perfect for law students, UPSC aspirants, and judiciary exam candidates seeking clear insights into India’s constitutional law evolution. Visit Lawgnan for full analysis.