Facts of the Case

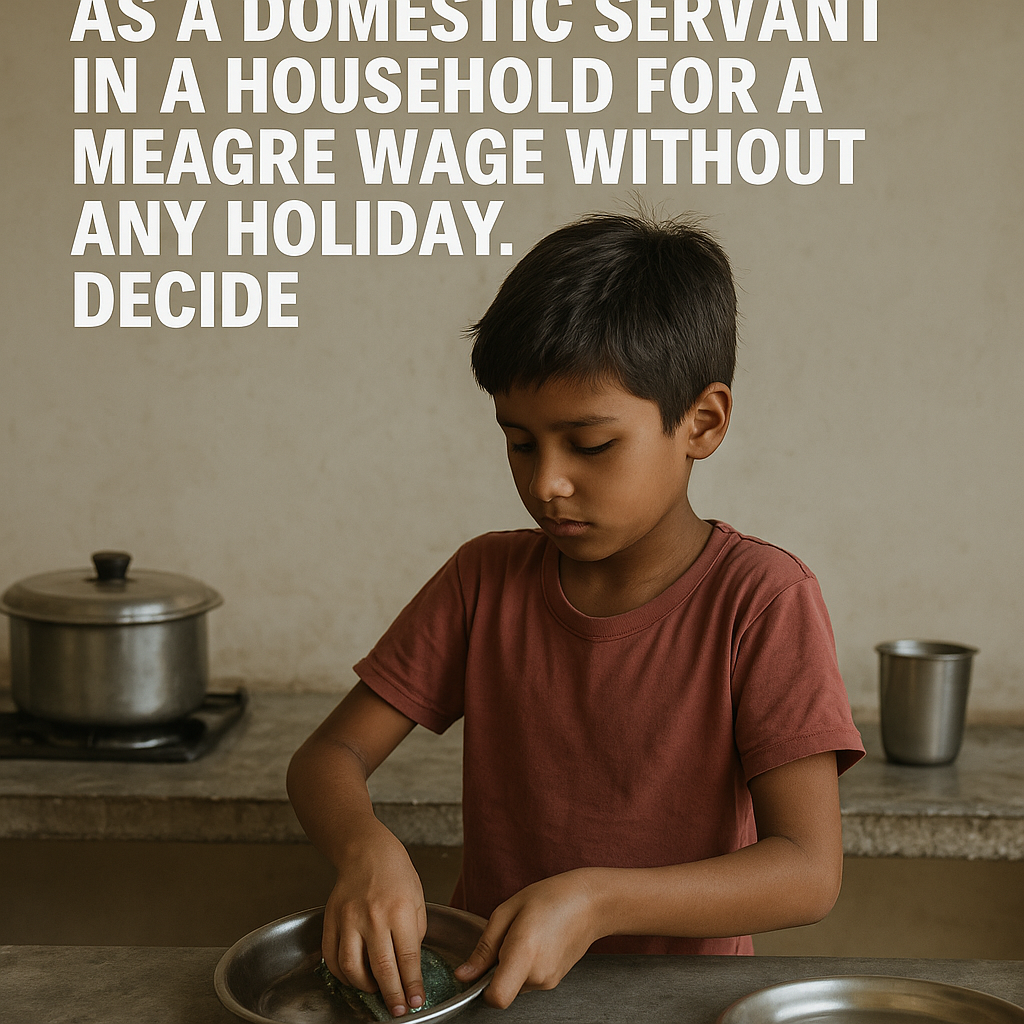

A 12-year-old child, hailing from a rural background, began working as a domestic servant in an urban household. The family employed the child to handle daily chores such as cooking, cleaning, washing, and taking care of younger children. In return, the household paid a meagre monthly wage.

The child had no fixed working hours and no holidays. Despite being underage, the family treated the child like a full-time adult worker. The child’s health, education, and dignity suffered. Upon inquiry, it was discovered that the parents had sent the child to work due to extreme poverty.

An NGO intervened after receiving a tip-off. They rescued the child and filed a complaint with the labour department and child welfare authorities. The employer claimed they were offering shelter and food as well and denied any wrongdoing.

Issues of the Case

- Whether employing a child below 14 years in domestic work violates the law?

- Does the absence of holidays and poor wages amount to exploitation under Indian law?

- What are the legal rights of a child under such employment conditions?

- Can the employer be held criminally liable for child labour and exploitation?

The key concern here is balancing economic hardship with the child’s right to protection and education. Poverty cannot justify the denial of childhood.

Principles and Related Case Law

Statutory Framework

- Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 (Amended in 2016):

This law strictly prohibits the employment of children below 14 years in any occupation or process, including domestic work. - The Constitution of India – Article 24:

It states that no child below 14 years shall be employed in any hazardous occupation. Domestic work is not traditionally considered hazardous, but the amendment to the law included it in the list of prohibited employment. - The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 (RTE Act):

Every child aged 6 to 14 has the right to free education. Employment during school-going age disrupts this right. - Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015:

The Act treats such child workers as children in need of care and protection. It also criminalizes those who employ children in contravention of the law.

Relevant Case: M.C. Mehta v. State of Tamil Nadu (AIR 1997 SC 699)

In this landmark case, the Supreme Court emphasized the state’s duty to prevent child labour and safeguard children’s rights. The court highlighted that mere economic benefit cannot override the child’s fundamental rights.

Judgment

The facts clearly indicate a violation of both statutory law and constitutional provisions. The employer engaged a minor in full-time domestic work, denied basic rest and holidays, and paid less than the minimum wage applicable to adult domestic workers.

Based on legal principles and precedents, the following judgment is appropriate:

- The employer is liable under the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act.

- The employer is also guilty of exploitation under the Juvenile Justice Act.

- Authorities must initiate prosecution, and the child must be rehabilitated and enrolled in school.

- A financial penalty and/or imprisonment, as provided under Section 14 of the Child Labour Act, should be imposed.

The court must direct the Child Welfare Committee to ensure long-term protection and education for the rescued child. Employers cannot escape responsibility by offering shelter or food.

The key takeaway is that domestic settings are no exception to child labour laws. Every child deserves dignity, education, and freedom from exploitation.